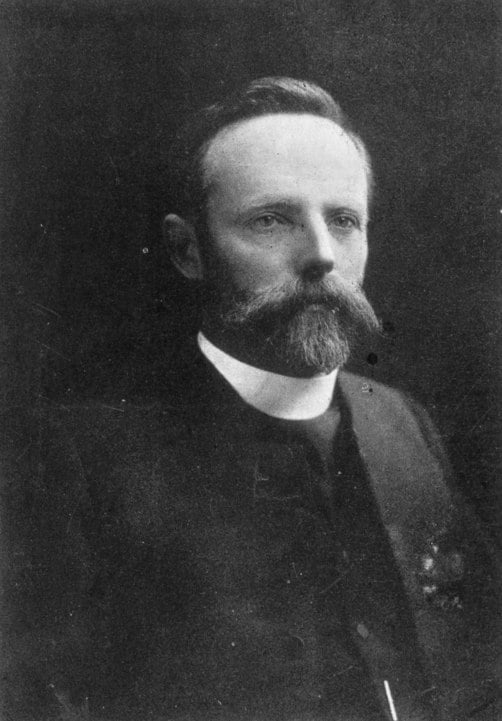

Name: David Garland

Epoch: Early 20th Century (the ‘Long Early Twentieth Century’)

Grouping Field: Humanities (Ideas Formatted as Ideas) and Social Science (Models)

Location Grouping: Individual’s Work Location

Map Coordinates: 27°27’04.5″S 153°00’02.7″E

Years At Location: 1911-1933

One Historical Setting: Canon David John Garland, Rector and Director of Immigration, St. Barnabas Anglican Church, Waterworks Road, Ithaca (1920)

David Garland had been Rector of Charters Towers, and a Canon of St James Cathedral, Townsville. He was the prime mover in the Bible in State Schools League in Queensland; in a long referendum campaign on religious instruction in state schools which was carried on 13 April 1910 by a large majority. Garland became Rector of Ithaca from 1920, and in that role was Director of Immigration for the Church in 1911-1933. He was President of the New Settlers’ League from 1926.

David Garland was a crusader for religious education in state schools in Western Australia and Queensland. It was a final political act in the very long battle between Church and Secular education, in the settlement of state education and the withdrawal of State Aid; as reflected in Wendy Mansfield’s assessment that “Garland was never loath to mix the spiritual and the secular.” Garland’s impact, though, went further into a cultural conservatism, ignoring the slow ‘winds of change’. World War I created in Garland a polemic figure who was no doubt kindly Anglican cleric, but his genuine garb of spirituality hides the possibility of a deeper assessment in political relations: character falsely excuses behaviour (a wider theme I will be exploring among Brisbane thinkers).

With Colonel A. J. Thynne, Garland was the Co-Founder of the Compulsory Service League. His outlook was colonial and imperialist, at a time when the war mentality was killing liberal thought (in terms of both die Kultur and Britannia). There are several nuances in Garland’s character, a very complex churchmanship, to which John Moses explains as Selbstverstaendnis, the biographical self-perception. This view is of Garland as a Gladstonian Imperialist, combined with a mixed ‘Orange’ and Anglo-Catholic theological outlook. Garland’s biblicalism in the state education movement speaks of the militancy of the Irish Protestant mindset (‘Orange’). His Anglo-Catholic conversion softens his outlook but it did not diminish Garland’s political militancy.

Moses refers to Garland’s Constantinian impulse in Church-State theory. After the expulsion of the Turks from Jerusalem, Garland was the first chaplain to celebrate the Eucharist in the Anglican chapel of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. During the 1919 rebellion in Egypt he provided liaison between the British military authorities and the Coptic Church, and was awarded the knighthood of the Gold Cross of the Holy Sepulchre by the patriarch of Jerusalem. These events go to the Constantinian Garland.

John Moses and George Davis argued the case for Garland as the true founder of the ANZAC tradition (and mythology), particularly given Garland’s New Zealand connections. Mark Cryle and other critics put a different case. Mansfield illuminates the debate by pointing to the publicly unspoken conflict in the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee between Garland and the Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia under (Sir) Bob Huish. Both sides recognise the tensions between one group of returned servicemen who were aligned with the faiths of the churches, and the other group aligned with what became the Returned Services League. Moses is correct in the legitimate fears that Garland shared with other Australian Anglican clergy of die Kultur, but both sides of the debate have not sufficiently recognised the problems in the concept of Britannia, and on both sides – the ‘Constantinian’ church institutions and the patriotic working class movement. Philosophically, the German realpolitik was ironically adopted in the frames of British and American idealism during the mid-twentieth century, extending from these World War I events, and the neo-orthodox religion was at the heart of that double-headed creature.

Mansfield, Wendy M. “Garland, David John (1864–1939)” (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/garland-david-john-62 78). Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre for Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 17 February 2016;

Cryle, Mark. ‘The tragic pageant of war’: ANZAC commemoration in 1917 and 1918, Social Alternatives, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2018, pp. 12-18.

Cryle,. “Natural enemies”? Anzac and the left to 1919, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, June 2014.

Cryle, Mark. The Architecture of Anzac Day: Shaping the 1916 observance in Queensland, AHA 2014: The Australian Historical Association 33rd Annual Conference. Conflict in History, 7-11 July, 2014.

Moses, John A. (Anthony); Davis, George F. Anzac Day Origins: Canon DJ Garland and Trans-Tasman Commemoration, Barton Books, Barton, A.C.T, 2013.

Moses, John. Email Conservation, 30 January 2020.

Perkins, Yvonne. Queensland’s Bible in State Schools Referendum 1910: A Case Study of Democracy, Department of History, University of Queensland, 2014.

Canon David John Garland, Archive: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. ([https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47013887]